Discovering the writings of Corwainer Smith in the early 1970’s was a life-changing revelation. At that time, neither his one novel, Norstrilia,nor any comprehensive compilation of his incredible short stories were in print.

For years, I would scour used bookstores in search of his stories, finding one of his stories in this or that compilation, in print, not in print, whatever. Needless to say, his writing had a profound effect on me and I have striven to create worlds, in music and art and words, as strange, as haunting, and, I hope, as full of love as his works, amidst the weirdness. Not that I come close in that regard: but one must aim high. Smith’s stories do not grow old. Interestingly, although he was almost unknown 40 years ago, he is regularly deemed the most influential science fiction writer of all time now. I recommend his books, Norstrilia and The Rediscovery of Man without hesitation.

From 1950 to 1966, stories appeared in mainstream science fiction magazines by an author named “Cordwainer Smith“. From the first to the last, these stories were acclaimed as among the most inventive and striking ever written, and that in a field specializing in the inventive and the striking. Their author was a very private man who did not want his real name to be known because he did not want to be pursued by SF fans. It was only after his death in 1966 that more than a handful of people knew that “Cordwainer Smith” was in real life Paul M. L. Linebarger.

Here is an article I found many many years ago and saved. I cannot find it anywhere else anymore, so I am taking the liberty of publishing it here. I make absolutely no claim to ownership or copyright. I am just publishing as a public service.

Christianity And The Science Fiction Of Cordwainer Smith by James B. Jordan Copyright © 1991 Originally published in Contra Mundum No. 2 Winter 1992

Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger

Paul Linebarger was born in 1913, the grandson of a clergyman. His father, an eccentric man, had served as a Federal District Judge in the Philippines, but had left this post to work full time for the cause of the Chinese republican reformer Sun Yat Sen, who became Paul’s godfather. Paul Linebarger grew up in the retinue of Sun Yat Sen, for his father stayed with Sen during his exile in Japan and throughout his career in China.

Linebarger spent his formative years in Japan, China, France, and Germany. By the time he grew up, he knew six languages and had become intimate with several cultures, both Oriental and Occidental.

He was only twenty-three when he earned his Ph.D. in political science at Johns Hopkins University, where he was later Professor of Asiatic politics for many years. Shortly thereafter, he graduated from editing his father’s books to publishing his own highly regarded works on Far Eastern affairs. [1]

After graduating from Johns Hopkins, Linebarger taught at Duke University from 1937 to 1946, but he also served actively in the Army during World War II as a second lieutenant. Pierce writes that “As a Far East specialist he was involved in the formation of the Office of War Information and of the Operation Planning and Intelligence Board. He also helped organize the Army’s first psychological warfare section.” [2]

He was sent to China and put in charge of psychological warfare and of coordinating Anglo- American and Chinese military activities. By the end of the war, he had risen to the rank of major.

In 1947, he became professor of Asiatic Politics at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.

Pierce writes, “Dr. Linebarger turned his wartime experiences into Psychological Warfare , still regarded as the most authoritative text in the field.”

As a colonel, he was advisor to the British forces in Malaya, and to the U. S. Eighth Army in Korea. But this self- styled “visitor to small wars” passed up Vietnam, feeling American involvement there was a mistake.

Travels around the world took him to Australia, Greece, Egypt, and many other countries; and his expertise was sufficiently valued that he became a leading member of the Foreign Policy Association and an advisor to President Kennedy. [3]

Linebarger was reared in a High Church Episcopalian family. Alan C. Elms’s sketch of the older Linebargers does not lead one to believe either was particularly devout. Paul’s father was evidently rather overbearing and placed many demands on his son. His mother was apparently rather self-centered and controlling. At the age of six, young Paul was blinded in his left eye as a result of an accident while playing, and the resulting infection damaged his right eye as well, causing him distress throughout his entire life. A sensitive, introspective, and apparently rather lonely and sickly youth, Paul Linebarger was to develop into a remarkable scholar, thinker, and writer. [4]

At some point in his life, Paul Linebarger became a strongly committed Christian. “He and [wife] Genevieve went to Sung Mass on Sundays, and he said grace at all meals at home. The faith extended and shaped his powerful imagination’ But he simply ignored contemporary religious movements, especially the secularizing ones directed to social problems. The God he had faith in had to do with the soul of man and with the unfolding of history and of the destiny of all living creatures.” [5]

The first science fiction story published by Linebarger, under the pseudonym Cordwainer Smith, was “Scanners Live in Vain”, in 1949. It had been written, however, in 1945. This story is a full-blown allegory of the coming of the New Covenant, and reveals a very sophisticated understanding both of the Biblical narrative and typology (e.g., the smell of roast lamb reminds the central character of the smell of burning people), and of the theological and philosophical tenets of the Christian religion. Linebarger must have become a serious Christian well before 1945.

Linebarger’s own psychological problems, as well as his keen interest in psychological warfare, caused him to explore modern psychiatry and psychoanalysis. These themes, as well as Christian philosophy and allegory, and also psychological warfare, run all through the science fiction he published as Cordwainer Smith.

Linebarger’s non-fictional works are these:

The Political Doctrines of Sun-Yat-Sen (1937)

Government in Republican China (1938)

The China of Chiang Kaishek (1941)

Psychological Warfare (1948; rev. 1954; reprint 1972).

Far Eastern Government and Politics: China & Japan (1954)

Linebarger’s interest in psychological warfare was closely related to his Christian views of ethics and history. Essentially, the purpose of psywar is winning without killing. The goal is to get an opportunity to speak to the mind of the enemy, and convince him that there are other ways to settle differences than killing people.

In Psychological Warfare , Linebarger focuses on the use of propaganda to weaken the resolve of the enemy and persuade him to give up. In his fiction, Linebarger matches the use of words with acts of kindness. This twin approach “true words and kind actions” becomes the essence of psychological warfare, both the military kind and the evangelistic kind.

Under the pseudonym Felix Forrest, Linebarger wrote two psychological novels: Ria (1947) and Carola (1949). Ria has been reprinted and is available in hardcover. In this novel we see portrayed something of Linebarger’s understanding of the world between the two great wars. Ria is a young American girl, and she typifies America: young, naive, kind, and rich. She is visiting Europe and encounters several people, who typify (a) the older Christian order in decline, (b) the new European occultism permeating Germany, and (c) the vigorous materialistic atheism of the new orient of Japan. There are many levels in this novel, but the most interesting may be its portrayal of these cultures as they meet and interact with each other.

In 1949, Linebarger’s novel Atomsk was published under the pseudonym Carmichael Smith. Atomsk is a spy thriller, and in it Linebarger openly sets forth his ideal of a Christian warrior. The main character explains early on that in order to defeat an enemy you have to love him. You have to want what is best for him, and if possible get close to him, win his confidence, and persuade him to change his ways. The novel shows the outworking of this Christian principle in international affairs. It is not in print, but if your library does not have an old copy, you can obtain it though inter-library loan.

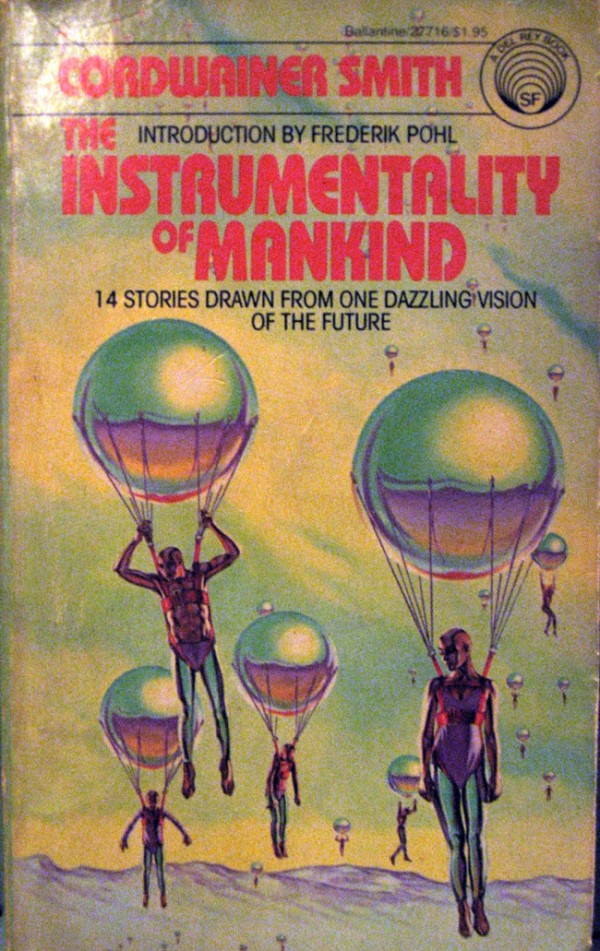

Finally, under the pseudonym Cordwainer Smith, Linebarger wrote a whole series of stories and novellas about a time in the far future when a suppressed Christian underground (the Holy Insurgency) faces a stultifying humanistic hierarchy (the Instrumentality of Mankind). It is through these stories rather than through his non-fictional work that Linebarger’s Christian understanding of war, culture, history, religion, and politics is encountered. The Cordwainer Smith stories are completely contained in the following five volumes:

The Best of Cordwainer Smith (Ballantine/Del Rey, 1975)

The Instrumentality of Mankind (Ballantine/Del Rey, 1979)

Norstrilia (Ballantine/Del Rey, 1975)

Quest of the Three Worlds (Ballantine/Del Rey, 1978)

“Down to a Sunless Sea” ( The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction , October, 1975)

The Style of Linebarger’s Science Fiction

Stylistically, “Cordwainer Smith” was a very odd writer, when compared with other science fiction writers. Some of his peculiarities found their way into what was called “New Wave” science fiction, which used experimental writing styles. What worked well for Smith, however, did not usually work well with his non- Christian imitators, largely I think just because of that difference in faith. Smith’s peculiarities arose from his medievalism, while the “New Wave” was often simply trying to be bizarre.

These peculiarities stem from several factors, of which I mention four that seem to me most important. First, Linebarger grew up in the orient and became familiar with the storytelling styles of non- Western cultures. He even translated some Chinese stories into English. Some of the abruptness and some of the elusive quality of his writing comes from this influence. He was not interested in portraying an “American” culture 20,000 years from now, but rather a human culture that had matured ” “evolved” if you will ” into new forms that would not simply be “Western”. There is, for example, a considerable amount of ceremony and ritual in his stories.

A second factor is mentioned by Arthur Burns: Linebarger “once said that Cordwainer Smith was a `pre- Cervantean’ ” the stories are like cycles of medieval legends, without the Aristotelian beginning- middle- and- end of classic tragedy, and certainly without the same structure as transposed into the modern novel, which Cervantes began. They are legendary cycles of the future, rather than future history, and were meant to be connected with and consistent with each other on the legendary and not the historiographic model.” [6] Many of his stories are told as legends. In “The Lady Who Sailed `The Soul'”, a mother tells her little girl the saga of Helen America and Mr. Grey-no-more. In “The Dead Lady of Clown Town”, the narrator seeks to separate what really happened on Fomalhaut III from various legends that have grown up around the event; he even discusses the artistic validity of various well- known paintings of the events.

A third factor is also mentioned by Burns: “Cordwainer Smith’s stories were a kind of important `playing’ (Paul was greatly impressed by Huizinga’s Homo Ludens ): through them are dotted irrelevant cryptograms, geographic allusions, and names transliterated from foreign languages.” [7] This is not quite accurate, in that the cryptograms, allusions, and foreign names are usually important clues to deeper and allegorical meanings in the stories. Linebarger does indicate in his prefaces and in his frivolous prelude to Norstrilia that his writing is, in part at least, for “fun”.

A final factor is his poetry. Over the years, Linebarger wrote quite a bit of poetry, publishing some of it occasionally under the name “Anthony Bearden”. Poems, songs, and ditties are found frequently in his science fiction tales. Nobody else in science fiction has his characters break into song!

The Content of the Instrumentality Cycle

All but three (some say five) of Linebarger’s science fiction stories belong in the same legendary future, generally called the “Instrumentality Cycle”. [8] Of the 24 short stories under consideration, eight are basically romances (love stories), [9] and many of the others have love as a basic theme. Here Linebarger continues a theme found in the fantasy stories of 19th and 20th century Anglican writers, the relationship between human romance and the romance of Christ and the Church. Augustine’s view of love as the bond among the persons of the Trinity is particularly important in Linebarger’s stories, since it is frequently love that keeps men from being seduced to evil.

Three dimensions of these stories call for our attention: the narrative, the allegorical, and the philosophical. First, while the stories vary in narrative strength, they are all well told, and hold attention. Curiously, the story with the least narrative credibility is the one novel, Norstrilia , but it must be born in mind that Linebarger had not finished tinkering with it when he died. [10] Most of the stories have to do with conflict and resolution. They are not puzzle or discovery stories, so common in science fiction. Indeed, at the narrative level they are no more science fiction than Star Wars . The science fiction element comes in at a different point, to be discussed below.

The second dimension of the stories is allegory. The fall of man is portrayed in “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard”; the flood is portrayed in “Under Old Earth”; and the coming of Christ and the defeat of the old law is allegorized in “Scanners Live in Vain”. “On the Sand Planet” is a sustained allegory that mixes and retells Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Dante’s Divine Comedy . Other stories retell events from history or literature. “The Dead Lady of Clown Town” is based on the history of Joan of Arc. “Drunkboat” is based on an event in the life of Arthur Rimbaud. The stories, however, stand up very well quite apart from the allegories.

The third dimension is the philosophical. There are very serious philosophical, social, and theological themes running through all of these stories. We shall close this brief introduction by calling attention to one of the most striking.

Linebarger was very concerned about what he called the “Pleasure Revolution”; that is, the tendency to use technology to reduce the risks of life, the pain of expanding dominion and growth. A society at ease is a society that has become “perfect too soon”, to quote one of his characters; [11] a society that has “tried to end history” to quote another. [12] Man’s high calling is to mature to the point of having dominion over the entire universe, but man tends to stop where he is and refuse to take further risks. Linebarger’s heroes are the men and women who “push the outside of the envelope” (to draw a phrase from Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff ), experiencing the pain and risk of dominion, and sometimes suffering permanent damage as a result.

A society that thinks it has all the answers is an autonomous society. It cannot move forward, for it denies the need for the “other”, for heteronomy, for social intercourse. This is the theme of romantic love on a larger canvas, and Linebarger explicitly connects the two in story after story. His prematurely perfected cultures are always essentially homosexual.

Man is called to deal with everything God puts before him. If he deals rightly, he grows; if he deals wrongly, he dies; if he refuses to deal with things at all, he stagnates and dies. This canon can be applied to virtually every one of the stories. When men reject further growth, God Himself intervenes to force men back to maturity. This is seen indirectly in several of the stories that deal with crisis points in this future history. As a result of some “unexplained and inexplicable” event, humanity is pushed away from autonomy.

The term “instrumentality” in Anglican theology refers to the priest who celebrates the sacrament: He is the “instrumentality” of God. Linebarger’s Instrumentality of Mankind is a kind of benevolent humanism that functions like a secular church, like the communist party, in overseeing human development. It is, however, essentially unlike anything in the world today, because humanity has grown, developed, and changed.

In its early days, the Instrumentality guides humanity well, but then stagnation sets in. Two answers are set forth. One is the Rediscovery of Man, the humanist attempt to reintroduce some diversity and risk into human life. The other is the Holy Insurgency, the rediscovery of the Old Strong Religion, advocated by the Underpeople who live in the catacombs. The conflict among these forces underlies most of the stories.

This “dominion” theme is virtually unique to Linebarger, and is very powerful and provocative. Man is called to take ever- expanding dominion over the universe. When he refuses, he dies. He must take the risk and experience the pain, if he is to mature. Characters who have faith and love survive; characters who do not love, or who don’t love strongly enough, are seriously crippled or even die.

This, by the way, is where the science fiction aspect comes in. In the future, as a result of expanding dominion, men are growing and changing. Human society then will be different from the way it is today. While much science fiction deals with the impact on society of particular technological inventions or discoveries, Linebarger’s approach is more psycho- social, in that he projects long- term social change and growth.

The central story in the cycle is the “novel” (actually just a long, pre-Cervantean narrative) Norstrilia . The theme of the novel is the Messiah, a theme addressed very indirectly. Briefly (and this is very brief): Rod McBan the 151st is heir of the Station of Doom. Before he can inherit this, he must pass a test in the Garden of Death. A snake- man stands ready to kill him if he fails. He does indeed fail, but the intercession of an unexpected visitor saves his life.

Rod makes an enemy of a local official. After escaping an attempt on his life, he retreats to a building kept on his property, the Palace of the Governor of Night, brought from the Egyptian planet Khufu II. In this replica of the Parthenon is a computer, called poetically a “godmachine”. The computer provides Rod with the false answer to his problem, by giving him financial advice so that overnight he becomes the richest person who has ever lived. He even purchases the planet Earth.

For his own protection Rod is taken to Earth. He is regarded as a messiah, and all kinds of people want his money for messianic projects of one sort or another. All Rod wants, however, is a postage stamp for his collection (a triangular Cape Colony stamp) ” he is, after all, only a teenager. He is befriended by the Underpeople, animals raised to intelligence as servants of humanity. The cat- girl C’Mell escorts Rod to the Department Store of Heart’s Desires. Here, in a room called Hell Hall, Rod is forced to come to grips with himself and his own depravity and guilt. Afterward, Rod is ready to meet E’telikeli, a bird- man who is primate of the Old Strong Religion.

The Underpeople have recovered the Scrap of the Book, and are guiding human civilization back to an understanding of the Three Forgotten Ones and the God Nailed High. E’telikeli wants Rod to use his money to help with this project, to which he agrees. In exchange, E’telikeli gives Rod a way to deal with his enemy on Norstrilia, a truer solution based on love and kindness.

At the end of the novel, the twin sons of Rod McBan are taking their ordeals in the Garden of Death. Only one survives. The surviving twin is sorely upset, but controls his grief, while his brother laughs his way to death under the influence of the killing drug. The last lines of the book are these: “Then the boy broke, just for a moment. He pointed at Rich, who was still laughing, off by himself, and then plunged for his father’s hug. `Oh, dad! Why me? Why me ?'” The dying boy is named `Rich,’ to show us the lost estate of Adamic humanity. Though he is dying, he laughs, showing us the blindness of sinful humanity. Isolated from life, he is “off by himself”. His brother, however, expresses the wish that he might be a substitute. The brother’s name is Ted, from Theodore, “gift of God”. In this subtle way, Linebarger shows us Who the Messiah really is. This, of course, is made more explicit in other stories.

Linebarger’s book Quest of the Three Worlds is a cycle of three stories that give expression to his thinking at its most mature, though in fictionalized and highly symbolic form. The overall story concerns a man named Casher who is seeking revenge against the savage revolutionaries who overthrew his uncle, a decadent dictator. In the first of the three stories that make up Quest , Casher visits a planet of gemstones (wealth) where he encounters a just and orderly government. In the course of this story we are given a “mirror for princes” as the hero learns what truly just human government should be like.

We move from “nature” (politics) to “grace” in the second story. Casher visits a planet of wind (spirit) where he is swallowed by an air-whale and then spat out again (as was Jonah, an image of resurrection). Now he is ready to receive the ancient truths concerning the Book and the Crucified God from a woman named T’Ruth.

In the third story Casher returns to his home planet of Mizzer (Mizraim; Egypt), a planet of sand (wilderness and trial), and there sets things right without taking vengeance. Then, in a story that combines Dante’s Divine Comedy and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress , the Christian hero sets out on his journey to a new Eden.

The Impact of “Cordwainer Smith”

Briefly in conclusion let me comment on the influence of these stories. First, they were all published in mainstream science fiction magazines, though sometimes the editors removed the explicitly religious parts. Second, these stories are very widely anthologized. I should say that the majority of collections of classic science fiction stories contain a Linebarger story.

Finally, Linebarger’s style and approach has had a great impact on the new generation of writers. Several of the most important of today’s science fiction writers, including Harlan Ellison and Ursula LeGuin, give him credit for showing them that it is possible to write really serious science fiction. At an SF convention in Austin, Texas, in September, 1985, interviews with current SF authors revealed that the two major influencers of modern SF are held to be Philip K. Dick and “Cordwainer Smith”, yet a good deal of hostility was generated at the suggestion that “Smith” was a Christian. [13] (There is a parallel here with J.R.R. Tolkien. The modern fantasy literature sprang from Tolkien, but for years most Tolkien fan- literature completely ignored the Christian dimension in his writing. Linebarger’s Christianity is a great deal more explicit and penetrating than Tolkien’s, however.)

In conclusion, I hope that these brief remarks have stimulated some interest in these stories. If I have motivated any of you to read Linebarger for yourself, I count this essay a success.

Bibliography

I. Larger studies of “Cordwainer Smith”.

Exploring Cordwainer Smith (Box 4175, NY 10017: Algol Press, 1975), 33 pages; $2.50. Collection of short essays and reminiscences.

Anthony R. Lewis, Concordance to Cordwainer Smith (New England Science Fiction Association, Box G, MIT Branch PO, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139; 1984), 90 pages; $6.00. An alphabetical listing of every name, term, etc. in the Smith corpus, with translations and interpretations.

John J. Pierce, Mr. Forest of Incandescent Bliss: The Man Behind Cordwainer Smith ( Speculation No. 33; photocopy obtainable from Mr. Peter Weston, 72 Beeches Dr., Erdington, Birmingham, B24 ODT, England). 23 pages. The best lengthy study of Smith, with a pretty comprehensive biography of Linebarger.

II. Shorter studies.

Alan C. Elms, “The Creation of Cordwainer Smith”, Science- Fiction Studies 11 (1984):264- 283. This is a valuable and well- researched biographical essay, particularly focussing on Linebarger’s early writings, and then moving to “Scanners Live in Vain”, “The Game of Rat and Dragon”, and Norstrilia . Elms views Linebarger’s writings as an exercise in psychotherapy (though he admits there was more to them than that), and he misses the point of the three pieces he discusses because he ignores the religious dimension. For the psychological dimension, however, this is a helpful essay.

Frank N. Magill, ed. Survey of Science Fiction (Englewood Cliffs: Salem Press, 1979). This is “Magill’s Masterplots” for SF. Gary K. Wolfe reviews The Best of Cordwainer Smith , focussing on the dialectic of romance and realism. Jane Hipolito reviews Norstrilia , focussing on its uneven literary quality. Walter E. Meyers reviews Space Lords , an early collection; its stories are contained in other later collections.

Alexei and Cory Panshin, SF in Dimension: A Book of Explorations (Chicago: Advent Publishers, 1976). Pages 222ff. briefly discuss Norstrilia . The Panshins completely miss the point of the novel, finding that it gives no answer to the questions it raises, and incredible as it sounds, state that “in Norstrilia , Smith lacks the nerve to imagine a larger power than the rigid and self- satisfied Lords of the Instrumentality” (p. 227).

Gary K. Wolfe, “Mythic Structures in Cordwainer Smith’s `The Game of Rat and Dragon'”, Science- Fiction Studies 4 (1977):144- 150. An attempt to bring Levi- Strauss and Eliade to bear on this story! In my opinion, a gross example of over- analysis, especially since Linebarger wrote this story in one afternoon.

Gary K. Wolfe and Carol T. Williams, “Cordwainer Smith”, in David Cowart and Thomas L. Wymer, eds., Twentieth Century American Science- Fiction Writers (Detroit: Gale Research Co, 1981). A brief survey, focussing on a dialectic of male and female attributes the authors find in Linebarger’s work, but generally ignoring the religious underpinnings.

“The Majesty of Kindness: The Dialectic of Cordwainer Smith”, in Thomas Clareson and Thomas Wymer, eds., Voices for the Future , Vol. 3 (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1984). A helpful but limited discussion. Includes some material on Linebarger’s earlier fiction. The authors miss the theological dimension, and thus their interpretations are askew rather consistently. For instance, discussing “Scanners Live in Vain”, they write, “Scanners cannot function without sacrificing a part of their humanity. Space is the realm of technology, earth of the organic” (p. 53). Actually, Scanners have to die in order to serve humanity. The work of Adam Stone, whose symbolic name has evidently been missed by the authors, is to bring resurrection and end the ceremonial law imposed by the Scanners.

Thomas L. Wymer, “Cordwainer Smith: Satirist or Male Chauvinist?”, Extrapolation 14 (1973): 157- 162. A sensible analysis of “The Game of Rat and Dragon”, dealing with the romantic and sexual dimension of the story. CM Notes 1. “Cordwainer Smith ” The Shaper of Myths”, in The Best of Cordwainer Smith (New York: Ballantine, 1975), p. xii.

2. Pierce, “Mr. Forest of Incandescent Bliss”, in Speculation 33, p. 7.

3. “Shaper of Myths”, p. xiif.

4. Alan C. Elms, “The Creation of Cordwainer Smith”, in Science-Fiction Studies 11 (1984):264-283. This essay tremendously overemphasizes the psychological motivations in Linebarger’s development, and underplays the religious.

5. Arthur Burns, “Paul Linebarger”, in Exploring Cordwainer Smith (New York: Algol Press, 1975), p. 9.

6. Ibid ., p. 9f.

7. Ibid ., p. 9.

8. Twenty- nine stories and one novel. Of these, one was written at the age of 15, and hardly counts. Four were completed by Genevieve Linebarger and, while they shed some light on the overall scheme, they are rather sketchy. There are, thus, 24 stories that merit most serious consideration.

9. I should count the following as having romantic love so central to the story that they can be counted as primarily love stories: “The Burning of the Brain”, “The Nancy Routine”, “The Lady Who Sailed the Soul”, “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard”, “The Ballad of Lost C’Mell”, “Think Blue, Count Two”, “Drunkboat”, and “The Crime and Glory of Commander Suzdal”. Walter E. Meyers has written, “‘ in the main Smith has only one theme: love. That theme, in its varied forms, is so rich a subject that thousands of years of storytellers have not exhausted it, but it is rare in science fiction’ No writer in the genre exercises greater skill in characterization or motivates those characters in mature human relationships better than does Cordwainer Smith.” Review of Space Lords in Frank N. Magill, Survey of Science Fiction (Englewood Cliffs: Salem Press, 1979), p. 2124f.

10. The Old North Australians practice population control by sending all their children to the “Garden of Death” at age 16 for a rite of passage. Only those who pass the test live. They refuse birth control as wrong. Being the wealthiest planet in the universe, however, they might have solved their problem by the practice of primogeniture, sending younger siblings offworld to make their own fortunes. This is not mentioned as an alternative. Similarly, the problem set up in the second half of the novel entails nothing that could not have been resolved in the office of Lord Jestocost in one afternoon’s session. Of course, had this been done we would not have the beautiful story! It should be noted that Linebarger was not happy with the novel, and thus released two sections of it as shorter novellas ( The Boy Who Bought Old Earth and The Underpeople ), while continuing to work on the complete version. What is published now was put together by his wife after his death.

11. D’Alma in “On the Sand Planet”.

12. E’Telikeli in Norstilia .

13. Interviews were conducted by Rev. George Grant, and his findings communicated to me in a conversation.